It’s not rare that a baby experiences a stroke around the time it is born. Birth is hard on the brain, as is the change in blood circulation from the mother to the neonate. At least 1 in 4,000 babies are affected shortly before, during, or after birth.

But a stroke in a baby — even a big one — does not have the same lasting impact as a stroke in an adult. A study led by Georgetown University Medical Center investigators found that a decade or two after a “perinatal” stroke damaged the left “language” side of the brain, affected teenagers and young adults used the right sides of their brain for language.

The findings, to be reported Feb. 17 in a symposium at the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) Annual Meeting in Austin, Tex., demonstrates how “plastic” brain function is in infants, says cognitive neuroscientist Elissa L. Newport, PhD, professor of neurology at Georgetown University School of Medicine, and director of the Center for Brain Plasticity and Recovery at Georgetown University and MedStar National Rehabilitation Network.

Her study found that the 12 individuals studied, aged 12 to 25, who had a left-brain perinatal stroke all used the right side of their brains for language. “Their language is good — normal,” she says.

The only telltale signs of prior damage to their brain are that some study individuals limp a bit and many have learned to make their left hands dominant because the stroke left right hand function impaired. They also have some executive function impairments — slightly slower neural processing, for example — that are common in individuals with brain injuries. But basic cognitive functions, like language comprehension and production, are excellent, Newport says.

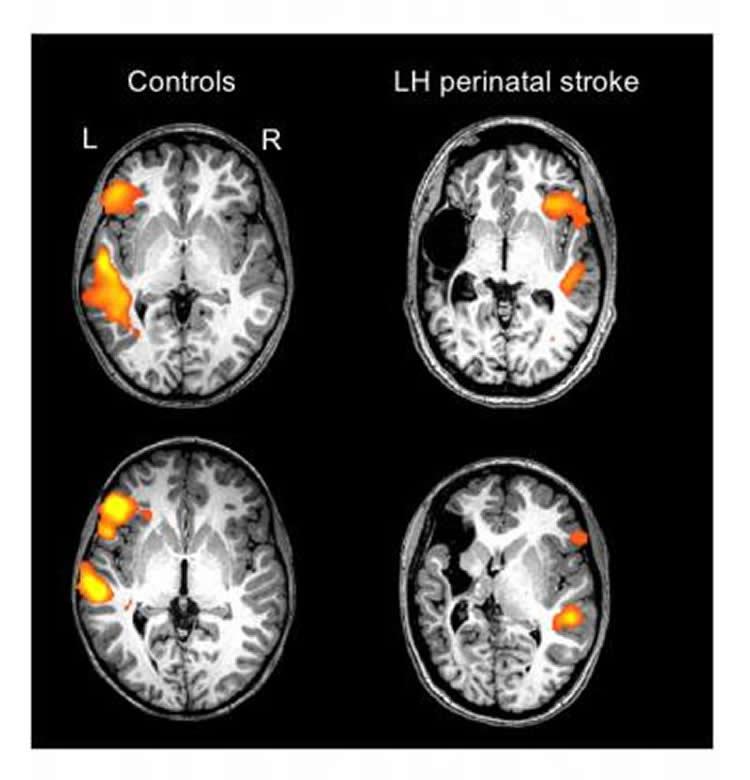

Furthermore, imaging studies revealed that language in these participants is all based in the right side in an exact, mirror opposite region to the left normal language areas. This has also been found in previous research, but earlier findings have been inconsistent, perhaps due to the heterogeneity of the types of brain injuries included in those studies, Newport explains. Her research, which was carefully controlled in terms of the types and areas of injury included, suggests that while “these young brains were very plastic, meaning they could relocate language to a healthy area, it doesn’t mean that new areas can be located willy-nilly on the right side.

“We believe there are very important constraints to where functions can be relocated,” she says. “There are very specific regions that take over when part of the brain is injured, depending on the particular function. Each function, like language or spatial skills, has a particular region that can take over if its primary brain area is injured. This is a very important discovery that may have implications in the rehabilitation of adult stroke survivors.”

This finding makes sense in very young brains, Newport adds. “Imaging shows that children up to about age four can process language in both sides of their brains, and then the functions split up: the left side processes sentences and the right processes emotion in language.”

Newport and her colleagues are extending their study of brain function after a perinatal stroke to a larger group of participants, and are looking at both left and right brain strokes and also at whether brain functions other than language are relocated and where.

Her group is also collaborating on studies that may reveal the molecular basis of plasticity in young brains — additional information that might help switch on plasticity in adults who have suffered stroke or brain injury.

In the ongoing study, Newport collaborates with other investigators at Georgetown University, as well as at Johns Hopkins University, Children’s National Medical Center, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and MedStar National Rehabilitation Network.